The domestic markets continue to rise, surpassing 23,500 at the beginning of this month. If the customary "Santa Claus Rally" occurs again this year, it may be enough to push the Dow above 25,000 by the end of the year. Of course, the last quarter is only half-finished, so there is plenty of time for the markets to retreat as well. Not to mention, same as the unflappable credo of every disappointed sports fan: "There's always next year!"

A market retreat is inevitable in every way, except its timing. Whether people decide that they have enough and now want to preserve it or if enough people uniformly time the market before a retreat to create what they fear remains to be seen. Based on the rise the market has enjoyed for the past 10 years, it could be a furious decline! Although 2008-09 decline was always characterized as a "once-in-a-lifetime" opportunity, I think many people do not believe it. Many are still on guard for another 50% retreat and playing both sides of the fence. Some are invested in cash because they expect the markets to plummet again and others are invested in cash because they want funds available to invest when the market declines.

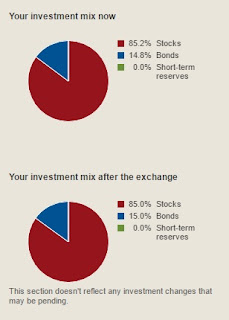

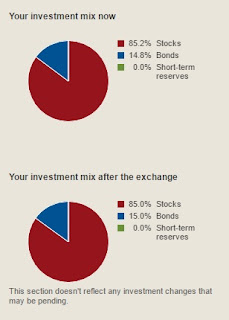

When I re-balanced last week, there was one thing more clear than everything else: active investing had far surpassed index investing. As it turned out, that is not my imagination or limited to my own profile. CNBC had even posted an article about it at the end of last quarter.

Because I am equally invested in Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund and Vanguard PRIMECAP Fund, the impact did not affect me much. But when I introduced the actively managed fund to my portfolio, I had indicated that if it trailed the index fund for two consecutive quarters that I would move that money back to the index. As it turned out, the index fund did outpace my active fund for two consecutive quarters and I strongly considered moving it back to the index fund. However, I knew there could be a time and day when market conditions favored active investing. It has been boasted for years, but this is the first time that I remember seeing a significant difference between the two.

Apparently, that time is now.

-------

I think one indicator of a slowing (is active surpassing the index) (also WFS and Equifax not being punished for their criminal activities)

[euphoria]

Chorus

"On a good day, we can part the seas. On a bad day, glory is beyond our reach."

Thursday, November 16, 2017

Monday, September 18, 2017

Active Outpacing Passive Investing (Reprint)

The Tide Has Turned: Active Outpacing Passive Investing

In the perennial race between active and passive investment management, there are signs of a shift. After several years of bringing up the rear, active performance has outpaced passive so far in 2017. Various factors suggest that it could stay out front for a few years.

This year has been the best for active fund performance since the bull market began, as it has bested passive more than half the time. About 54 percent of active managers have beaten their benchmarks overall so far in 2017; about 60 percent did so in July.

Meanwhile, though long-depressed inflows into active funds have shown new life recently (they had their best week in 30 months in July, taking in $3.5 billion), money keeps gushing into exchange-traded funds. (Vanguard investors in index funds and ETFs now own nearly 5 percent of the S&P 500.) Real dominance by active management would be marked by a reversal of this tide.

This won't happen, of course, until after active management has shown a sustained performance advantage.

Various considerations suggest the potential for this, including:

Past trends. Historically, active management's comebacks have been multiyear rather than single-year. Though passive has reigned supreme over the past six years, active won the race for six years in the 1990s and from 2001 to 2011. Just as passive management has done best in up markets, active's potential for superior performance tends to be higher in difficult markets. Thus, active did well in the difficult market of the mid-1990s, and passive took the lead during the tech boom late in that decade.

Today's narrow bull market. When the bull's starting point is pegged to the ascent that followed the financial crisis of 2008, the current bull market is now nine years old, the longest since World War II (though the argument could be made that this bull is actually of shorter duration because the market didn't hit a new high until 2013). Regardless, those anticipating a new market cycle are more likely to be gratified with each passing month, as the price/earnings ratio of dominant names have risen to ethereal heights.

This market has a weakness that isn't acknowledged widely enough: It's being driven mainly by six large-cap stocks — Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Google and Johnson & Johnson (the Big Six.) When the market has gone up in the past couple years, much of the gain has been because one or more of these stocks has appreciated. As of early September, year to date, all of the stocks have had robust double-digit gains, with Facebook's shares appreciating nearly 48 percent and Apple's about 37 percent.

If these few bulls stop running and the herd doesn't find new leaders, this result could be an ensuing difficult market — the kind where active managers do best.

Increasing opportunities for contrarian managers. With huge investment from index funds and ETFs, the Big Six have amassed a collective market capitalization of $3.4 trillion — greater than the total value of the bottom 1,115 stocks in the S&P 1,500 — the lower large-cap companies. If the Big Six falter, money pouring into them will presumably find other places to go.

But even if this happens, empowering the bull market to continue, passive management's fixation on the S&P 500 will continue to provide increased opportunities for active managers seeking value opportunities among lower large-cap companies. And some of these 1,115 orphans are fairly attractive.

Labels:

CNNFN

Saturday, August 12, 2017

The Full Motley -- 3Q, 2017

We passed through the first six months of 2017 without any major incidents affecting the stock market as the Dow soared up past 22,000, before falling a little this week. But true to the cliche, "what goes up must come down." Granted, those who have bought & held that philosophy since 2008 might disagree as the market's 2009 low-water mark may not be seen again. Someday, I will discuss the term "financial gravity" in relation to personal investing, but for now, I need to re-balance my 401(k), which I did on Tuesday, a day ahead of my usual target date of the 10th.

Not surprisingly, my Total International Stock Index Fund was way up! Overall, I am looking to increase my exposure to international markets, so I have been pursuing some changes to my asset allocation, which would significantly impact how I rebalance my account, but the discipline and philosophy of it would remain the exact same.

Not surprisingly, my Total International Stock Index Fund was way up! Overall, I am looking to increase my exposure to international markets, so I have been pursuing some changes to my asset allocation, which would significantly impact how I rebalance my account, but the discipline and philosophy of it would remain the exact same.

In addition to my Total International Stock Index Fund, my Total Stock Market Index Fund and PRIMECAP Fund were up slightly (I had to move out significantly more from the actively-managed fund than the index fund, which may or may not mean anything for the future of the market). The pot was then evenly split between my Explorer Fund and my Total Bond Market Index Fund, except for a small portion falling into the High-Yield Corporate Fund (which I understand have been increasing in popularity, if not in value, quite a bit lately).

As I have said in the past, when I move my allocation targets, I make the decision at least one quarter before implementing those changes. Therefore, my next update might be the last one under my current asset allocation! If I decide to change my allocation, then the 1Q18 update should see a high infusion of assets into my Total International Stock Index Fund.

Which would make sense because there will be an important comparison at that point, which coincides with my blog's 9th anniversary fittingly. I look forward to sharing those results at that time!

Not surprisingly, my Total International Stock Index Fund was way up! Overall, I am looking to increase my exposure to international markets, so I have been pursuing some changes to my asset allocation, which would significantly impact how I rebalance my account, but the discipline and philosophy of it would remain the exact same.

Not surprisingly, my Total International Stock Index Fund was way up! Overall, I am looking to increase my exposure to international markets, so I have been pursuing some changes to my asset allocation, which would significantly impact how I rebalance my account, but the discipline and philosophy of it would remain the exact same.In addition to my Total International Stock Index Fund, my Total Stock Market Index Fund and PRIMECAP Fund were up slightly (I had to move out significantly more from the actively-managed fund than the index fund, which may or may not mean anything for the future of the market). The pot was then evenly split between my Explorer Fund and my Total Bond Market Index Fund, except for a small portion falling into the High-Yield Corporate Fund (which I understand have been increasing in popularity, if not in value, quite a bit lately).

As I have said in the past, when I move my allocation targets, I make the decision at least one quarter before implementing those changes. Therefore, my next update might be the last one under my current asset allocation! If I decide to change my allocation, then the 1Q18 update should see a high infusion of assets into my Total International Stock Index Fund.

Which would make sense because there will be an important comparison at that point, which coincides with my blog's 9th anniversary fittingly. I look forward to sharing those results at that time!

Saturday, July 1, 2017

The Dow, the Nasdaq, and the S&P 500 (Reprint)

What's the Difference Between the Dow, the Nasdaq, and the S&P 500?

Turn on the news and you'll see these three stock market indices. Here's the difference between them and why it matters.

Jay Jenkins (TMFJayHJenkins)

Jul 8, 2014 at 1:00 p.m.

"The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJINDICES:^DJI) was down 0.74% as of 1:05 p.m. EDT, falling back under the 17,000 mark. The S&P 500 (SNPINDEX:^GSPC)was down just slightly more, while the Nasdaq (NASDAQINDEX:^IXIC) plummeted by 1.5%."

Days like (this) can leave beginning investors confused by the mechanics of the markets. How bad is the market? Is it 0.7% bad like the Dow or S&P, or is it twice that bad as we see in the Nasdaq?

To understand exactly what's happening in the market today, let's break down each of these major indices and drill down into why each is different and also somewhat the same.

The Dow Jones

The Dow Jones Industrial Average is the oldest, best known, and most followed of the major stock market indices. It is comprised solely of 30 large-cap companies. These companies represent a huge array of American business -- from consumer facing to business-to-business, tech to manufacturing, domestic to international, and everything in between.

Two concepts make the Dow so popular. First, the companies in the index are huge, and taken together they legitimately represent a huge swath of the U.S. economy. So while there are thousands of publicly traded companies, these big boys are sufficiently large to effectively act as a proxy for all the other enterprises.

Second, the Dow components are nearly universally recognized household names. With the likes of Coca Cola (NYSE:KO), McDonald's, or IBM, investors know that these companies are the real deal, with the size, scale, and presence in the economy to accurately stand as a proxy for the overall markets.

The Dow does have a quirk, a remnant of its history of more than a century. The index is price-weighted, meaning that companies with a higher share price have a larger impact on the Dow's movements. That's why Visa (NYSE:V)has an 8.1% weight versus just 1.59% for Coke.

The S&P 500

The S&P 500 takes a slightly different approach to represent the movements of the broader markets. The index covers the largest companies that trade on the New York Stock Exchange or Nasdaq Stock Market, weighted by market cap.

The S&P 500 chooses component companies based on a few basic criteria. The stock must trade at sufficient volume with adequate market liquidity. The company's market cap must be above $5 billion. At least 50% of the company's stock must be part of the public float.

The S&P also attempts to mirror the diversity of the largest companies on the NYSE and Nasdaq; if 10% of the largest companies are in manufacturing, then the S&P will attempt to maintain 10% of the index in manufacturing companies.

There are two other obvious yet notable contrasts with the Dow. First, there's the number of component stocks, 30 versus 500. The S&P is a much broader measure of the markets and captures a greater percentage of the U.S. economy. That said, the lower you move in market cap, the less impact those stocks have on the index as a whole. So in many instances, the Dow and the S&P track each other very closely.

Second, unlike the Dow, the S&P is not price-weighted. Instead, it weights its component companies by the actual size of the company in the market. This eliminates some of the odd Dow pricing when a stock with a high stock price but relatively lower market cap makes a large movement in either direction.

Both of these differences creates a smoothing effect on the S&P -- it's just not as volatile as the Dow.

The Nasdaq

First, let's clarify exactly what we're talking about here. The Nasdaq (NASDAQ:NDAQ) is a stock exchange, similar to the New York Stock Exchange. It was, in fact, the first all-electronic stock exchange. That is not what we're here to discuss.

We're talking about the Nasdaq Composite, another market proxy based on certain stocks being publicly traded. The Nasdaq Composite is based on the 4,000+ stocks being traded on the Nasdaq Stock Market. The difference is subtle, but it's worth understanding to avoid any confusion.

Generally, the Nasdaq Composite is a good proxy for what is happening in the tech segments of the markets. The vast majority of the companies trading on the exchange are tech, which leads to this generalization.

That said, there are certainly a respectable number of companies from a broad range of industries also traded on the Nasdaq Composite -- from banks to airlines to coffee shops. But these nontech components remain a small contingent in this index.

Like the S&P, the Nasdaq is weighted by market cap, thus avoiding some of the odd pricing situations seen with the Dow.

So which way is the market heading?

When I see the headlines at the end of the day's trading, I tend to gravitate to the S&P 500. To me, the 500 component stocks weighted by market cap is the best representation of the broad market movements.

If you're interested in tech, then you may have more interest in the Nasdaq. Just know that you're not looking at the market in a broad sense with that index, you're looking disproportionately at the tech segment.

The Dow, of course, is and will remain the primary index used in the news and by most public market commentators. It's the oldest, it's the best known, and in truth it's good enough to serve in that role. But, as a Foolish investor, always keep in the back of your mind that it has just 30 stocks and it's calculated with that oddball price-weighted system.

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

CNNFN: Half of Americans are spending their entire paycheck

Half of Americans are spending their entire paycheck (or more)

by Anna BahneyJune 27, 2017: 12:17 PM ET

http://money.cnn.com/2017/06/27/pf/expenses/index.html

Nearly half of Americans say their expenses are equal to or greater than their income, according to a new study from the Center for Financial Services Innovation. And for those 18 to 25 the percentage is over half, up to 54%.

"Half of America has no financial cushion," says Jennifer Tescher, president and CEO of CFSI, which released the study. "They are living really close to the edge."

Of the 25% who say they have too much debt, 96% report being stressed. This kind of financial stress has lasting health effects for those constantly working to cover the nut, says Tescher. "We can't deal with their health problems if we can't deal with their financial health."

With one out of every two people maxed-out with expenses, it is likely you or someone you know. "It's your co-workers, the receptionist, the guy mowing your lawn, the woman who takes care of your kids."

Maybe it's you.

Why we're struggling

Perhaps we're overspending? Maybe the gig economy isn't working for us?

Certainly we can all do the hard work of cutting back on our expenses, says Tescher. But she says the results of this study show something more structural than individual spending.

"People are spending a shockingly large amount of income on housing. They have to pay for transportation to get to a job. These costs are going up while their wages stay the same."

Another major contributor, according to the study, is irregular income. Nearly 40% of those who spend as much or more than their paychecks have volatile income, which means it varies from day to day, week to week, month to month.

On average, families experienced income volatility five months out of the year, according to the recent book, "Financial Diaries: How American Families Cope in a World of Uncertainty," by Jonathan Morduch and Rachel Schneider, who is also at CFSI.

And in those volatile months, income could range by 25%, meaning $1,000 in income could be $1,250 one month, $750 the next.

How do we get out of the rut?

New financial tools aim to help people manage their money more efficiently. Like Activehours, which allows you to get part of your pay ahead of payday in a way that is not a payday loan. There is also a tool called Even, which, in addition to helping you budget, does just that: it evens out your pay from high periods and shoots it to you when you have lower periods.

But Tescher doesn't see tech tools as a magic bullet.

"We have a series of structural challenges in this country that require policy solutions," she says. "We need to remove the stigma of talking about money problems and make it clear that a lot of people are struggling."

Wednesday, May 10, 2017

The Full Motley -- 2Q, 2017

Another quarter has passed, and I submitted another quick rebalance yesterday after market close. As busy as I have been lately, my established pattern of rebalancing meant that it did not take much time to plug the numbers into my reliable spreadsheet and determine how much money to move around in order to get those investments back to my target allocation. In this case, I moved money from my international stock index fund and my actively managed stock fund and put small portions into my bond index fund, stock index fund, my actively managed small cap fund and my high yield bond fund.

I was delighted to see that the international markets were climbing up since I have been moving money from my domestic stock index fund into an international index fund in my Roth IRA on a weekly basis, attempting to build that portion to a significantly higher percentage (as well as direct earnings out of the domestic market while it is still riding a high off the election, also the prior eight years).

In other news, a few of my triple-leveraged ETFs had stock splits or reverse stock splits at the start of the month. It benefited me because my initial purchase of the $SPXL was for only 25 shares, so after it had doubled, I was not able to easily split that amount in half. Of course, then I got greedy and I wanted to keep more shares after the sale than a split. I expect to reach that amount later this month, but I am of course risking the chance that the market may turn down and I may miss my opportunity. But that is the risk and reward relationship of investing. It is the main reason that I rebalance quarterly because, left to my own decision-making, I would (more often than not) make the wrong decision. I suffer from the human condition.

I was delighted to see that the international markets were climbing up since I have been moving money from my domestic stock index fund into an international index fund in my Roth IRA on a weekly basis, attempting to build that portion to a significantly higher percentage (as well as direct earnings out of the domestic market while it is still riding a high off the election, also the prior eight years).

In other news, a few of my triple-leveraged ETFs had stock splits or reverse stock splits at the start of the month. It benefited me because my initial purchase of the $SPXL was for only 25 shares, so after it had doubled, I was not able to easily split that amount in half. Of course, then I got greedy and I wanted to keep more shares after the sale than a split. I expect to reach that amount later this month, but I am of course risking the chance that the market may turn down and I may miss my opportunity. But that is the risk and reward relationship of investing. It is the main reason that I rebalance quarterly because, left to my own decision-making, I would (more often than not) make the wrong decision. I suffer from the human condition.

Sunday, April 30, 2017

Another Day, Another Dollar

The dichotomy between time and money forever fascinates me. While people fully recognize money as currency, time can be viewed as another type of currency (albeit, in loosely applied terminology). Both are non-renewable resources in that once they are spent, they are gone. But time, unlike money, could be called an equalizing currency. Whereas the wealth gap has proven that money is not equally distributed among its users, time certainly is. Every person's day has the same 24 hours, each with the same 60 minutes as everyone else's day. Every person has a projected lifespan within a short range, although it is merely an estimated lifetime, much like projected returns are an estimate.

It may be a bit anecdotal (and if there have been many exceptions, they could have been forgotten) but I have seen several examples of upward mobility firsthand through those I have known. In most of their cases, the people valued time above money. In less glorified or heroic terms, they may have put more time into trying to prove (mostly to themselves) that they were right, so I do not want to give the impression that I am mentioning some superhuman people, either blessed by divine promise or naturally more gifted than everyone else around them (like almost every role Matt Damon has had). These are just regular people who were more driven at a younger age than I was. [link]I remember thinking that their ambition was misused[/link], but now that we are further along in our stories, I can wholly admit that who was wrong -- and it was not them.

I used to carpool with a colleague with whom I have lost touch (even in this hyper-connected world of today) that shared with me how his entire work day was directly tied to his paycheck. He further explained that he had marked his calendar at work to show the first five workdays of each month went to his home, because that sum equaled his mortgage. He said that, although our lunch breaks were 45 minutes, his lunches were only 5-7 minutes because that was the average cost against his current wage. He had allocated every item in his budget to his work week. It prevented him from engaging in certain activities because they were either cost prohibitive or simply not cost efficient, but he also knew how to splurge. He was just hyper-aware whenever he was splurging (and, to his credit, those activities generally benefited his wife and kids). While he may have been an extreme example, his time was correlated to his currency (and truthfully, I only remember this discussion occurring on one evening trip home, so this concept probably did not consume all his time).

I fully accept that I have been given every opportunity to succeed, probably at a much higher rate than I have used. I had a father who was very proficient in decision-making, whether in his personal life, in his financial life, or for a group of unique individuals. Both sets of grandparents were very successful, especially for the height of the American Dream when wealth distribution and other opportunities were considerably more equal. Likewise, my mother has plenty of financial aptitude herself. Therefore, I am well aware that my personal finances were skewed by considerable help, especially from my mother and paternal grandmother.

However, the biggest help that I have received from them is not any monetary gifts. It was how to manage my own finances properly, how to value a dollar as objectively as possible, and how to relate time to money (and vice-versa). Passing along that knowledge is my primary goal through these pages and in related discussions in real life.

Regardless, an old adage rings true: you can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make it drink. I have learned a useful distinction between helping friends financially and just giving them handouts. If they ask for my help, then I simply give them my knowledge. If that was not the help they wanted, then I feel safe in assuming they just wanted my money, not my help. When they are interested in learning from me and applying my knowledge, then I am far more giving financially as well because I know that using my money to help them save more of their own money, those dollars will be used productively. Even then though, I know firsthand that those dollars are a minor benefit compared to gaining the wealth of knowledge of wealth itself.

It may be a bit anecdotal (and if there have been many exceptions, they could have been forgotten) but I have seen several examples of upward mobility firsthand through those I have known. In most of their cases, the people valued time above money. In less glorified or heroic terms, they may have put more time into trying to prove (mostly to themselves) that they were right, so I do not want to give the impression that I am mentioning some superhuman people, either blessed by divine promise or naturally more gifted than everyone else around them (like almost every role Matt Damon has had). These are just regular people who were more driven at a younger age than I was. [link]I remember thinking that their ambition was misused[/link], but now that we are further along in our stories, I can wholly admit that who was wrong -- and it was not them.

I used to carpool with a colleague with whom I have lost touch (even in this hyper-connected world of today) that shared with me how his entire work day was directly tied to his paycheck. He further explained that he had marked his calendar at work to show the first five workdays of each month went to his home, because that sum equaled his mortgage. He said that, although our lunch breaks were 45 minutes, his lunches were only 5-7 minutes because that was the average cost against his current wage. He had allocated every item in his budget to his work week. It prevented him from engaging in certain activities because they were either cost prohibitive or simply not cost efficient, but he also knew how to splurge. He was just hyper-aware whenever he was splurging (and, to his credit, those activities generally benefited his wife and kids). While he may have been an extreme example, his time was correlated to his currency (and truthfully, I only remember this discussion occurring on one evening trip home, so this concept probably did not consume all his time).

I fully accept that I have been given every opportunity to succeed, probably at a much higher rate than I have used. I had a father who was very proficient in decision-making, whether in his personal life, in his financial life, or for a group of unique individuals. Both sets of grandparents were very successful, especially for the height of the American Dream when wealth distribution and other opportunities were considerably more equal. Likewise, my mother has plenty of financial aptitude herself. Therefore, I am well aware that my personal finances were skewed by considerable help, especially from my mother and paternal grandmother.

However, the biggest help that I have received from them is not any monetary gifts. It was how to manage my own finances properly, how to value a dollar as objectively as possible, and how to relate time to money (and vice-versa). Passing along that knowledge is my primary goal through these pages and in related discussions in real life.

Regardless, an old adage rings true: you can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make it drink. I have learned a useful distinction between helping friends financially and just giving them handouts. If they ask for my help, then I simply give them my knowledge. If that was not the help they wanted, then I feel safe in assuming they just wanted my money, not my help. When they are interested in learning from me and applying my knowledge, then I am far more giving financially as well because I know that using my money to help them save more of their own money, those dollars will be used productively. Even then though, I know firsthand that those dollars are a minor benefit compared to gaining the wealth of knowledge of wealth itself.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)