I am in a mentally abusive, love/hate relationship with Twitter. On the one hand, it is a toxic cesspool of negativity, fueled by inaction and targeting intolerance, yet blissfully unaware of its own hypocrisy. On the other hand, it is a fascinating glimpse inside the minds of certain people whose public personas vary greatly. Several years ago, Taxicab Confessions was a popular HBO show for its dirty laundry that people would never air in public otherwise. Similarly, Twitter handles are a guise for people to feel enough anonymity to say the things that they have too much civility (or that they lack the courage) to say publicly.

Tweets are limited in characters (pause to accentuate the pun), so Twitter is not an exchange of deeply formed thinking, yet it can provide insight on the reactionary beliefs of its users. If an excited utterance is admissible as an exception to hearsay, then there is some value to this aspect.

That said, I like to analyze certain arguments to pinpoint the fallacy of them. One discussion that captured my attention recently was revolving around the use of phrase "generational wealth." Numerous tweets use generational wealth to portend the elimination of the middle class. Many others use it to discredit good advice, generally treating difficult and impossible as synonymous terms. Then, it seems as though some people will set themselves on fire to prove no one cares that people are burning.

The first problem with generational wealth is that those with it are discredited by those struggling without it. The bigger problem is that the discussions fail to understand the other side’s perspective. I saw a tweet asking users whether more money would solve all their problems. One response noted that “the only people saying no are people with money.” It was true enough, but the irony is that he sounded as though people with money were not reliable sources. To the answer to the question as stated, the only reliable response would be from people with money.

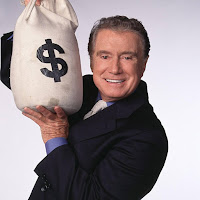

|

| How I read this meme |

Almost immediately, I made the connection that the arguments surrounding generational wealth should really focus on generational knowledge instead.

I thought back to my childhood, complaining to my mother about whatever money I wasted on a useless endeavor or how much it would cost to repair a mistake, and she would empathetically reply, “Yup, that was an expensive lesson.” For the most part though, my parents steered me in the right direction the first time. Certainly, I have had some expensive lessons in my life, but there were a lot of experiences, especially in terms of personal finances, that I got right the first time. How? Because the first thing I was told to do was the right way to do it (or at least one that had been proven as reliable).

When I worked at Vanguard, I was instructed to share Vanguard’s investment principles (“We Believes”) with our callers as applicable. I am the type of person that, if I am telling someone else to do it, then I want to know that it works. Hence the short stints in selling Variable Universal Life insurance products or in a MLM pyramid. Sure enough, all of Vanguard's We Believes were reliably sound wisdom.

People can discredit my wealth or success through the same means of opportunity or inheritance, but my response is to question whether they actually think I would have received either if I had not proven myself capable of managing them? The catch is that they do not know my parents or grandparents. I do, and the honest answer is that I would not have.

This response works somewhat better than asking someone how they would spend a fictitious inheritance, because the responses are wildly disjointed from their actual actions a lot of the time. Apparently, they think there is a magical number (just above their reach) at which point responsibility begins. "If I had that much money, then I could manage it easily too."